Yoko Ono: Visionary for Peace and Symbol of Creativity

Fan-Submitted Writing, Photos, and Collaboration

This is a collection of information gathered about Yoko Ono. We hope that you enjoy this content, and if you’re looking for additional resources, we suggest Yoko’s own website (as the official resource), the wikipedia page (for the most up-to-date information), and the collection of Yoko Ono media at amazon for related discography and merchandise. We’ve also compiled some fun facts and stats from the U.S. Census Bureau about the name Yoko Ono. Have fun, and enjoy!

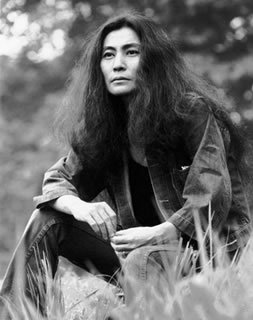

Yoko Ono Biography

by Shahbeila Bateman

Artistically misunderstood, derisively known as the most famous widow in the world and vilified as the catalyst for the breakup of the most famous music group of all time, Yoko Ono in actuality is an uncompromising artistic visionary who was already an avant-garde superstar before she met John Lennon. Today, Yoko is finally recognized as an influential artist who pushes the boundaries of the art, film, music and theatre media. The present time marks a renewed resurgence of interest and celebration of her work. She has recently received high media profile due to the simultaneous reissue of her music catalog (including a boxed set) on the Rykodisc specialty label as well as for the premiere of her off-Broadway theatre piece Hiroshima. However, these achievements obscure her body of 16 films made between 1964 and 1972, some in a collaborative effort with her late husband.

Yoko Ono (whose first name translates to “ocean child”) was born on February 18, 1933, in Tokyo, the eldest of three children born to Eisuke and Isoko, a wealthy aristocratic family. Her father was a frustrated pianist who held degrees from Tokyo universities in mathematics and economics. In 1935 he became head of a Japanese bank in San Francisco, and as a result, he did not meet Yoko until she was two years old, since she stayed behind in Tokyo with her mother.

When Yoko was 18, her father was appointed the president of a bank in New York as the family settled in the affluent suburb of Scarsdale, N.Y. Attending the prestigious Sarah Lawrence College in New York, Yoko dropped out to elope with her first husband, Toshi Ichiyanagi. It was while living in New York’s artsy Greenwich Village that Yoko discovered the world of avant-garde artists. Once absorbed in the scene, she began her lifelong association with art starting with informal events then segueing into poetry while developing her fascination for conceptual pieces. Alienated as an “artistic radical” for years her work was ridiculed or ignored. That began to change once she started her working relationship with American jazz musician/film producer Anthony Cox, the man who would eventually become her second husband.

Cox financed and helped coordinate her “interactive conceptual events” in the early 60’s. According to the artist these events; “Demanded a response and some input from the observer rather than answering all the questions.” Her most famous piece was the “cut piece” staged in 1964, where the audience was invited to cut off pieces of her clothing until she was naked, an abstract commentary on discarding materialism (i.e., disguises) for the natural (i.e., the real)underneath. Yoko’s work often demands the viewers’ participation and forces them to get involved. A famous example is from her “This Is Not Here” exhibit from the early 70’s. One section of the exhibit included a living room completely painted white with the objects; armchair, grandfather clock, desk, television set, even an apple, cut completely in half. The viewer must “complete” the scenario with a reference memory of the “whole” object. In other words, art is a two-part process–what is presented by the artist and how it is interpreted by its audience.

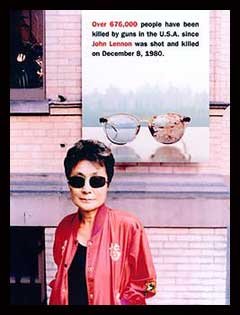

The marriage between Ono and Cox was a tempestuous liaison that produced one child–a daughter named Kyoko who was born on August 8, 1963. By this time, Yoko was heavily influenced by the extended and repeated image work of Andy Warhol, Dali inspired surrealism and Dadaesque absurdity. The latter is evident in events such as having her audience pay a shilling to hammer a nail in a board–a satirical jab at consumerism.

The notoriety of Yoko’s events, as well as her involvement with the radical 60’s avant-garde art collective Fluxus, created an interest in her works in the United Kingdom. This interest precipitated her visit to England in 1967.

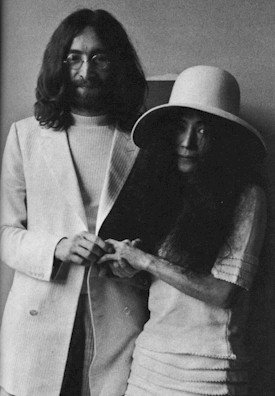

Yoko’s life forever changed when she met Beatle John Lennon at an exhibit of her work at the Indica gallery in London. Lennon, in addition to being a pop culture icon, was also one of the most brilliant creative minds of all time, with an art school background. The mental stimulation between the two developed into a strong friendship which eventually blossomed into romance as well as a creative marriage.

By 1968, their affair was public as both of their marriages disintegrated. A bad side effect of Yoko’s collapse of her marriage to Cox was that he “kidnapped” their daughter during a weekend custody visit. For almost 30 years, Yoko did not see her long-lost daughter Kyoko, but they were eventually reunited.

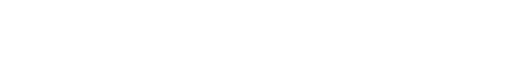

Since John’s death, Yoko has remained active, releasing three music albums, engaging in two concert tours(one which featured her and John’s only son Sean leading the backup band)and composing two off-Broadway musicals–the most recent being Hiroshima.

It was during the mid-sixties that Yoko began to explore motion picture as another extension of her art. Her first film, 1964’s Film No. 1 a.k.a. A Walk To Taj Mahal breaks down the barrier between camera and audience as the camera takes on the viewers point of view walking through a snowstorm.

Subsequent films can be subdivided by themes. The first of which can be grouped together by her fascination with the aspect and form of the (usually nude) human body. She almost seems to enjoy demystifying the sexual aura by featuring repetitive shots of isolated body parts. This is best exemplified by the minimalistic approach of her film Bottoms which consists of a series of frames made up of nothing but hundreds of naked backsides. This theme continues in 1968’s Up Your Legs Forever, which follows camera movement across the form of one aspect of a woman’s body, as well as in her 1970 collaboration with Lennon entitled Fly. The latter depicts the movement of a fly along the landscape of a nude female body, augmented on the soundtrack by a voice piece by Ono that is used as the “voice” of the fly which correlates with the movement of the insect. The most infamous of the nude pieces is Smile –a 1969 collaboration with Lennon that consists of slow-motion photography of a close-up of Lennon’s penis achieving an erection, complete with a soundtrack of industrial and mechanical noises. 1968’s Freedom can also be included in the body series and is also the first to incorporate a blatant feminist theme which she would expand on the following year with Rape. Freedom focuses on a woman pulling on the clasp of her bra, with the film ending just before it’s removed. According to the essay “Yoko Ono: Objects; Films”: “Ono plays with our sense of anticipation by constructing a metaphor for the liberation of the female body and self.”

The next subcategory of Ono films are conceptual. Erection and Apothesis both share themes of movement and change. Erection is a pixilated film using stop-motion photography at different speeds to document the construction and erection of a building at the same angle to present–in the words of the “…Objects; Films” essay: “…An almost organic form growing before our eyes”. Apothesis follows the Lennon’s ascending to the sky in a hot air balloon through cloud banks to symbolize a transcendental journey.

The last subcategory of Ono films can be described as documentaries. Bed -In documents the Lennons honeymoon peace event in an Amsterdam hotel. While Two Virgins and 1971’s Imagine gives outsiders a view of the relationship and their recording process respectively. Sisters O Sisters is a straightforward concert film of Yoko (backed up by John and The Plastic Ono Band) performing at a benefit concert in Ann Arbor, Michigan for jailed political activist John Sinclair.

When once asked what kind of artist she was, Yoko answered, “I deal with music of the mind.” Her imaginative concepts presented in her films may not be hummable in everyone’s hit parade. However the thoughtfulness in examining new ways to explore issues strike a unique and resonant chord in the minds of many.

Sources: Fawcett, Anthony. (1981) John Lennon: One Day At A Time. New York: Penguin Yoko Ono: Objects, Films. (1988) catalogue to Yoko Ono’s show at the Whitney, New York, N.Y.

Another Yoko Ono Biography

by Ted Pirro

Yoko Ono is one of the most famous widows in the world. Her name is synonymous with the Beatles and John Lennon.

She began making films in the 1960’s and made substantial contributions to the avant-garde genre of film. When Yoko Ono began this part of her life, she was already an established artist playing an active role in the world of music, most well known by her “primal scream” or high pitched wails.

In the early 1960’s, Ono became part of a group known as Fluxus, whose artists were “dedicated to challenging conventional definitions in the fine arts, and conventional relationships between artwork and viewer.”

The artwork that Yoko made in the early 1960’s required the viewer to complete the process. “Painting to See a Room Through,” made in 1961, was a canvas with an almost invisible hole through which the viewer could see the room. “Painting to Hammer a Nail In,” also made in 1961, was a white wood panel that the audience hammered a nail into with an attached hammer.

In the mid-1960’s Yoko began to write mini film scripts. She contributed three films to the Fluxfilm Program in 1966. Two of these films, Eyeblink and Match, are one shot films shot at 2000 frames per second. She also included No. 4, or Bottoms, in her contribution.

Yoko continued to make films through the early 1970’s, many of which she collaborated with her husband, John Lennon. Her films can be divided into themes. The first of which, like bottoms, consists of a close examination of the naked human body. The second category are theoretical films. They have a theme of movement and change. The last category is documentaries. Bed-In made in 1969, is the filming of the peace event Ono and Lennon staged on their honeymoon.

Yoko Ono can be viewed as a radical artist, someone who requires an open mind in order to have her work appreciated. She stretches the limits of what society views as acceptable and never ceases to create an opportunity for the viewer to step back and reflect.

Just Imagine

In the 60s, Yoko Ono married John Lennon and campaigned for peace in Vietnam. More than 30 years on, she’s still irrevocably linked to her dead husband and America is once again at war. Here, she talks to Andrew Smith about marriage, art and inner peace.

Sunday November 4, 2001 The Observer

How does it feel to have the whole context of your life and work changed in an instant? And then frozen in another? Yoko Ono was a star of the New York avant-garde art scene when Lennon walked into her show at the Indica Gallery in London in 1966, grabbed one of the exhibits, a green apple on a glass plinth, cutely labelled ‘Apple’, and took a bite out of it. She was cross. ‘Oh, I was terribly cross,’ she says. ‘He’d been showing his sophisticated artist side, and then he suddenly did that and I thought, oh dear…’

Reminded that the value of the exhibit probably increased a thousandfold, she laughs. Her voice surprises in its sing-song pleasantness. She has turned 68, but could pass for 20 years younger. Ono will not be what I expected in any sense, and the answers to those opening questions will be even less straightforward.

‘It was funny. I didn’t know what to make of my feelings for him. He was very sexy. In that first meeting, he showed a sense of humour and very complex sides of his personality. But for me, he was also… I think that in the crowd I was in, in the avant-garde, there were a lot of guys who were extremely interesting as composers, but I didn’t feel anything coming from them. No kind of guy thing. He had a charge, a force. And I felt that.’

She’s sitting at the mosaic dining table in the kitchen of the rambling top-floor apartment she shared with Lennon in the Dakota building, the gothic apartment block where Polanski filmed Rosemary’s Baby and outside which the former Beatle was shot by Mark Chapman as he stepped through the entrance arch on 8 December 1980. There are Magrittes and Warhols on the walls and, down the hall in the ‘white room’, the piano on which ‘Imagine’ was written. Like so many before, I will stand in front of it resisting an urge to play something, while not being quite sure where either impulse (to play, not to play) is coming from. Today would have been his 61st birthday and is also that of his son, Sean, who will be a sullen presence in the background of this first meeting. I wonder if he’s angry with his mum for working today.

Lennon’s birthday aside, it’s a strange time to be visiting. I’ve seen the remains of the World Trade Center and realised with horror that the lonely, cathedral-shaped spear of steel frame that defied the destruction will be the first iconic image of the 21st century. Ambling through Central Park towards the Dakota on this cold, clear morning, I came across several dozen people singing a shrill chorus of ‘Give Peace a Chance’.

And I wondered, what’s changed? Where is John and Yoko’s Nutopia? According to the newscasters, the last time such a concentration of American bombers had been assembled was in March 1945, when Tokyo was razed to the ground and 83,000 people were killed.

Strangely, she was there.

Lennon had been born into a chaotic working-class family, but Ono (born 18 February 1933) was an heir to privilege. Her father was an aspiring concert pianist turned banker, while her mother came from the wealthy Yasuda banking clan, and she was schooled at the Japanese equivalent of Eton. Nevertheless, during the war, they struggled as everyone else. She remembers being woken at night and hustled into a bomb shelter, where the group would listen to the series of regular thuds coming closer, then fading like the steps of a retreating giant into the distance. At one point, the children were evacuated to the country, where the city kids were despised by the farmers they were billeted with.

‘It was very frightening,’ she replies, when asked if the experience marked her permanently. Kids must have had to learn to rely on themselves and contain their feelings. ‘Oh of course, I have that side, too. Even now, I’m always thankful that we have something to eat and a roof over our heads. Because there was a time when we were starving. I also tend to keep paper bags and boxes and things, I can’t throw them away. My daughter thinks it’s funny.’

She has said that she was ‘always afraid’ as a child and always felt herself to be an outsider – which is odd, because, as we shall see, she grew into a remarkably fearless adult.

Moving to the US with her family after the war, Ono went to art college.

Her father was passionate about Western classical music and had made sure she was schooled in it, while her mother taught her Japanese idioms – making her at the time one of very few people in the West with an intimate understanding of both. In her early twenties, she hit Manhattan and married the Japanese piano prodigy, Ichiyanagi Toshi, subsequently falling in with the clique of avant-garde composers gathered around the likes of John Cage, David Tudor and La Monte Young (whose first collection of musicians went on to become the Velvet Underground). Ultimately, this movement would be known as Fluxus, and Ono, as a pioneer of ‘performance art’, would be a dynamic force within it.

As the 60s began, she reluctantly moved back to Japan with her husband, but, unable to work properly, she was miserable and is said to have attempted suicide in 1962, at the age of 29. Eventually, she met the American Tony Cox, who had admired her paintings, and returned to New York, where he became her promoter. Friends had expressed doubts about his advisability as a partner, and this – in keeping with the pattern of her life -proved to be a volatile, if professionally successful partnership. They had a daughter, Kyoko, whom Cox would finally wrest custody of by citing Ono and Lennon’s dissolute, drug-sodden lifestyle, and later disappear with. Yoko wouldn’t see Kyoko again for 25 years, and if you look at news footage from the time, was clearly seen to be heartbroken, but before then her career had taken off. Which is how she came to be invited to swinging London in 1966 (‘It was, like, bang! – I couldn’t believe what was going on there’) and to have her own fateful exhibition at the Indica gallery in November 1966.

The tales of her camping out in front of Lennon’s house until he let her in are not true, she says. ‘I didn’t even know where he lived. That’s not my way of doing things. And also, I wasn’t that intent on connecting with him. The point is that now people read those stories and think it’s beautiful. Women send me letters saying, “Oh, it’s so beautiful to know that you were so forceful and thank you for doing that for John”, and stuff like that. But I went to Paris after we met and said that I wouldn’t go back to London. I didn’t want a relationship at the time, because I wanted freedom for my work. And I don’t like the idea that I’m creating a situation where women think that they have to stalk a man to get them. It’s really serious! No, don’t stalk them!’

She dissolves into laughter again. From everything I’ve read and heard, he seemed the more besotted at that point. ‘Well, I thought that and I thought that I didn’t want to get too involved in it. It seemed like the wrong situation at the wrong time. I was already aware that there was an entourage looking at me like, “What are you trying to do?” and I thought, I’m not trying to do anything, leave me out of this. It’s like, something told me this is bad news – and it was!’

People have asked what John Lennon saw in her. One of the things, certainly, was her art. There is a growing body of critical opinion which holds that meeting Lennon was the worst thing that could have happened to Yoko Ono as an artist in her own right. Her poetry’s never been up to much, but her broad musical sensibility and feral singing voice were intriguing enough for the titanic jazz saxophonist Ornette Coleman to invite her to join him for a performance at the Royal Albert Hall in 1966 (‘Only if we do my compositions, I told him’) and some of her Zen-touched visual work has been inspired.

A pioneer of conceptual art as now practised by Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, Jake and Dinos et al, she was about tickling the imagination. A chess set, in brass, with all the pieces enamelled white, is entitled Play It By Trust ; a glass case containing four glass keys becomes Glass Keys to Open the Sky . Blood oozes from under the lid of a brass box labelled Family Album (this one post-John). A grey line on canvas is accompanied by the handwritten suggestion that ‘This line is part of a very large circle’. At the time of that first London show, she had just been on the evening news while making her Bottoms film, which depicted 365 perambulating bums, accompanied by the subjects’ commentary on the experience. The sense of play and mischief is what got lost in the mainstream shift that followed Ono’s liaison with Lennon, while the avant-garde shunned her for ‘selling out’.

Ono appears taken aback when I ask why she always wears shades (today’s are tinted blue), sputtering, ‘I don’t know. I did that even when John and I were together… probably.’ Actually, I don’t think she did. She’s a fascinating woman, but a difficult interviewee. She smiles and laughs, but turns hostile in a beat, often in anticipation of a question you’d never even considered asking, and is fiendishly hard to engage with. On occasion, I suspect her of using the subject of John, which is safe because everything’s been said, as a shield to protect herself from scrutiny. Perhaps this is what it’s like being frozen in time by a man with a gun: only much later am I able to recognise the contradiction between the openness and generosity of her political ideas and her anger with ‘the world’ she once accused of killing her husband. I’d imagined this to have been uttered out of immediate hurt, but when I ask if she still believes it and whether she excuses herself (and the other ‘poets’, perhaps?) from being part of ‘the world’, things will take a bewildering turn. Ono may well be as tough to do business with as McCartney, the other Beatles and her stepson Julian complain that she is.

The most interesting stuff comes up where I least expect it, around a retrospective exhibition, Yes Yoko Ono, and a new album, Blueprint for a Sunrise , which was made with her son Sean’s deft band, IMA. She was going to call the record Sondown , she says, because she liked the play on words, but was pulled up short. ‘I thought, I don’t want to write a song called “Sondown”. I thought, my God this is terrible. I always think in terms of multiple meanings. I don’t want to lay that on my future, or my son. So I thought, no, I have to write something about “Sonrise”.’She laughs. ‘Then I thought, but there’s no son rise here – I mean, yes, Sean is doing OK, but the point is in the society.’

You think that you can bring things into being with your songs, I ask? She mentions ‘Walking on Thin Ice’, the tune which she and Lennon had been working on and was in his cassette machine when he was shot in the archway of the Dakota.

‘Afterwards, I was always thinking, why did I write that? Because you know they’re playing it all over the world, and I was actually walking on thin ice after John’s passing. I thought, did I set this up?’

A belief in that kind of power must be frightening for an artist. ‘It’s scary, but you know in hindsight, a lot of things did happen that I was not aware of at the time.’

Are there other instances where you think your work changed the future? ‘Well, I think ‘Imagine’ was prophetic, in a very positive way. I think it’s all right that it’s not fashionable or faddish and might seem simple.’

Only afterwards does it dawn on me quite how wildly untrue this statement is, even if the song did piss off the Nixon administration and seem challenging for a while at the time. I enquire after two of the most striking tunes on Sunrise – ‘I Want You to Remember Me’ and ‘Rising II’, both of which are funky little dramas centred around a woman being attacked by men. She seems to have heard me suggest that the stories being told are about her in a literal sense, where they actually sound more generalised to me.

‘I object to that. If a woman writes about a domestic situation, everyone automatically assumes that it’s about her. I’m speaking for victims. In ‘Rising’, I was thinking about a little girl, an abused little child – which was probably me. I mean, that’s not what happened to me, though.’

She draws a clever parallel between people and the environment, the world generally. ‘It’s the same sort of logic in a way. We tend to misuse an object that is passive.’

We fall to talking about the sleeve, which has her dressed as the ‘Dragon Lady’ of Chinese legend. It’s what the British press used to call her, referring to the last empress of China, who history paints as a tyrant, but was actually a fierce defender of her people against the colonising British, according to Ono.

‘We learnt about her in school in Japan and she was always quoted as an example of how cruel women can be when they get power, and I totally believed it. And it was like I was in the same position of protecting a country, which was the Nutopia. Which they did not like. It was a kind of conceptual country that I was protecting. I thought the parallel was interesting. There were many monstrous things that were said about me.’

Her notoriety is ascribed to her being not only a woman, but an Asian woman (not long after Pearl Harbor and Korea and during the war in Vietnam) and, worst of all, an avant-garde artist who’d snagged one of the most blindly revered men in the world.

‘I was trying their patience, without wanting to. I understand now and I think that it’s interesting that all of us together had to go through that to come to a kind of awareness of each other. Now when people meet an Asian woman, I don’t think they automatically think of Madame Butterfly or geisha.’ She laughs brightly. ‘And the attitude to women is changing, which is not my doing, but I was part of it.’

All of which is probably right, though the conspiratorial closeness which unsettled the Beatles in the studio probably also made others uncomfortable. Not that it’s anyone else’s business, but it seemed to come mostly from John and could look a little desperate.

‘Well,’ she says, ‘he was extremely insecure in that way. I think he didn’t want to leave me alone – that’s one thing. But also, we were in love, like teenagers. We wanted to be together. And I think that, in his mind, probably, he knew the others were not happy about it. But in his usual way, he was saying, “Forget it! Too bad!” Their relations had been strained anyway after his “We’re bigger than Jesus” remark. And he felt guilty, but also he was angry. But the anger was repressed anger, because he couldn’t blame anybody else! But there was also the feeling of being caged in by the band at that point.’

When she talks about him like this, you feel Lennon’s presence at the other end of the table, still alive for her and smiling affectionately back, and I become aware that few people are forced to continually rake over the death of a close partner the way that she is.

Two days later, we’re shoeless in the ‘white room’ and Yoko is sternly instructing me that she doesn’t want to talk about the recent split from antique dealer Sam Havadtoy, her partner of many years, which strikes me as amusing because I didn’t know about such a split until she mentioned it – though I had intended to ask how anyone can sustain romantic ties with her when the relationship with Lennon is still so present. Anyway, now she asks me not to mention that, or the fact that she’d explained her attraction to John in terms of his sexiness. It’s early and she’s tired, because Sean and his young and notably more gorgeous than him girlfriend left for home in LA today and they stayed up late, chatting.

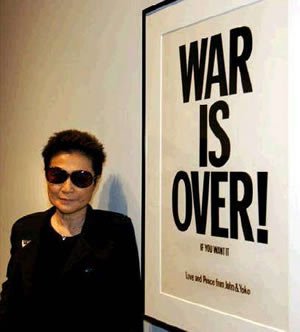

We talk more about John and spend some time on the Fluxus years, much of which is interesting, but all of which I’ve heard before, then come to the war on terrorism. After I’d left the other day, her PA had called to say that, contrary to what Ono told me, her most recent artwork was not the spectacular piece currently receiving rave review in Yokahama; an old Nazi box car such as Jews were transported in, with mounted machine guns and a powerful searchlight streaming to the heavens through a hole in the top and myriad bullet holes, as recorded ambient noise swarms around it. Rather, it consisted of two things I would find down by Times Square, which turned out to be a pair of billboards containing stark black lower-case type over a pure white background, quoting portions of the lyrics to ‘Imagine’. Surrounded by all the corporate logos and screaming neon lights, they’re effective, and we’re on to the subject of the war on terrorism. Ono feels that she’s been there before and learnt a thing or two.

‘Some people may feel that it’s necessary to strike back, and when someone is striking out you don’t go and stand in front of them and try to stop them. I’m saying, “We don’t fight for peace, we have to be peaceful.” Which is different. In the 60s we fought for peace, when the Vietnam war was on. We were against the cops and against the politicians and there was a lot of waving banners and all that. And I think in a way, just as they were enjoying that machoism of war, we were enjoying the machismo of being anti-war, you know? So I thought, not this time, it’s too complicated a situation. We cannot enjoy the machoism of fighting for peace. I felt that I wanted John’s fans to know that. You can stand for peace, but not fight for it.

‘There were some factions of flower children who felt – rightly -extremely angered by injustice and so they wanted to wake up the politicians, bomb the White House, whatever. And John and I were saying, you can’t do that, that’s not how we do it. They would say the result is the most important thing. But no, the result is important, but so are the means. So I think our side felt that John and Yoko were too tame and optimistic. And felt that was Yoko’s fault.’ She laughs. ‘But kids were hurt. John was kind of angered that innocent kids were led to demonstrate because the leaders told them too, et cetera. So this time we don’t fight for peace. And if the truth be told, the people who are fighting today, probably think that they are fighting for peace, too. Probably we are all imagining the same thing in the end, but we have different ideas of how to get there.’

And our time is up and I go away feeling strangely deflated. It’s lovely to think that we might all want the same thing, or even imagine the same thing in the end, but we don’t. I don’t want the same thing as George Bush, or the president of Exxon or the people who make the bombs being dropped on Afghanistan right now. Pretending that we do, flowerchild-style, looks to me like another way of avoiding inconvenient truths, part of a legacy of self-delusion that Ono’s generation left to mine; just one more way of getting people to shut up and stop asking questions. Which, you frequently get the feeling, is what Ono wants more than anything else.

Later, on the phone, I finally get a chance to ask whether she still feels that John was killed ‘by the world’. ‘Yes,’ she states flatly. But what do you mean by that? ‘I think I mean what I said.’ But the world didn’t kill John literally. Aren’t you part of the world? ‘I don’t think I have anything to add,’ she concludes sharply.

So I ask whether her 60s ideals have survived the decades intact, or been tempered by time? ‘Look,’ she says, ‘we’re growing up together, the human race. And we’ve discovered a lot of things that we didn’t know. We’re finding our way. Instead of thinking about doomsday all the time, think about how beautiful the world is. We’re all together and together we’re getting wiser.’

Another lovely thought. The irony is that she sounds kind of angry as she says it.

Source: Sunday November 4, 2001 The Observer

See fun facts and stats about the name Yoko Ono!

This information about Yoko Ono brought to you by Namedat.

We love to share articles from our community with others! If you love to write and have an idea for an interesting article, let us know and we’ll consider it for publishing.